Here We Are, Here We Are

The camera is a very large rectangular box, with lens and black cloth bellows at the front. Using Polacolor Polaroid film, it makes brilliantly colored photographs that are twenty inches by twenty four inches in seventy-five seconds. Built into the back, the motorized Polaroid processor has rollers that squeeze and spread chemicals onto positive and negative paper. There are two doors: one where the bellows are attached to insert pods of chemicals and rolls of positive and negative, and another at the back covering the viewing glass that the photographer looks through. It weighs 200 pounds and is perched on a dolly so it can be cranked up and down and rolled around. The processing system works like the old “peel apart” Polaroids of the fifties and sixties–after seventy-five seconds,the positive image is ready to be peeled apart from the negative. Happily, the image doesn’t have to be coated. This camera runs like a dream when I am relaxed and jams when I am anxious. When I am overtired or upset, its motor comes to a grinding halt.

The 20×24 was designed by Edwin H. Land, the inventor and founder of Polaroid. Only five were built– hand made in Dr. Land’s personal workshop. The first one was unveiled at a Polaroid stock holders meeting in April 1976. In my view, the camera represents a special time in corporate American history when the founder of a public company could build a product with few commercial applications simply because he wanted to. There were no bottom line considerations. All but one of the skilled machinists who tooled the 20×24 have retired and have not been replaced. The machine shop where the cameras were built is quiet now. Spare parts were never made and patterns for parts, if they ever existed, were misplaced long ago.

Almost twenty years before Dr. Land unveiled the 20×24, I graduated from Tufts University in Medford, MA. In 1959 most girls like me were going to be elementrary school teachers and I didn’t want to be one. I wanted to be a writer. I went to New York City where I got a job at Grove Press. It was the pivotal experience of my life. I was secretary to Dick Seaver, the managing editor of the Press and The Evergreen Review,and typed letters to Henry Miller, Samuel Beckett, Jasper Johns. As part of my job I arranged the first poetry readings of the sixties with Allen Ginsberg, Charles Olson and Robert Creeley. I was a handmaiden and I considered it a more than adequate role. The thought that I was leading a vicariously creative life by helping these men never occurred to me–even after I formed the Paterson Society to arrange poetry readings at colleges across the country and to publish small books of their poetry.

After a year in New York, I became confused by the creative life I was observing and the conventional life I thought I should be living. I moved back to Boston and I continued to arrange poetry readings, but I still didn’t see how I could have a creative life myself. In desperation, I went to Boston College and got a degree in elementary education. I began teaching fifth grade in a public elementary school in Concord, Ma. I read haiku and short poems by Creeley and Ginsberg to my students. My homeroom class was never organized enough to pledge to the flag and to read from the Bible before the bell rang. Finally, one of the parents told me,” Yo u shouln’t be doing this. I work for a place called Educational Developm ent Corporation. They match far-out teachers with scientists to develop curriculum materials.”

I immediately announced to my poet friends I was a photographer. No o ne laughed and I was on my way. Bob Creeley called to say that he needed a photograph for his new book. Charles Olson said, “Come on down to Glo ucester.” Gordon Cairnie said he could use portraits of poets for the wal ls of his Grolier Book Shop. Gary Snyder and Philip Whalen went camera s hopping in Kyoto and shipped me a Mamiya C-33 in a soft leather case.

I took my camera everywhere and photographed everyone and everything. All the time. In my first apartment, (it had one room) I painted two walls black and set up a darkroom across from my daybed. In those days n obody knew anything about chemicals and the need for ventilation. After n ine years, I put together a collection of portraits of my friends in my house, Elsa’s Housebook–A Woman’s Photojournal, published by David R. Godine in 1974. But I didn’t try to support myself as a photographer. I did editing and writing jobs to pay the rent. In th e sixties, it was still possible to live on the edge.

From the very beginning of his company, Dr. Land had given photographers Polaroid cameras and film and had collected their work. He had close relationships with Ansel Adams, Paul Caponigro, Philippe Halsmann and Ma rie Cosindas and believed that his company would benefit from his commitm ent to artists. Eventually, his support was formalized into the Polaroid Artists Support Program which encouraged selected photographers to use P olaroid materials in exchange for prints for the Polaroid Collection. Hav ing seen work made on the 20×24, I was dying to use the camera. Bob Roden at Polaroid agreed to subsidize a session on February 7, 1980 when Allen Ginsberg and Peter Orlovsky came to Boston to read their poetry and were staying with me.

I was supposed to make a temperate ten or twelve images. We did several nudes while Bob, Roger Gregoire and Peter Bass, who ran the camera that day, shook their heads and wondered what was going to happen next. I ha d always worked with small format cameras and didn’t realize large camera s should be treated thoughtfully as the ponderous instruments they are. I snapped away as if I were using 35mm film. No wonder they were aghast. By the time I called it quits I had made 30 images. The amaryllis we had brought to the studio went from tight shut to full bloom under the studi o lights. I was hooked.

I wanted to photograph my husband Harvey Silverglate and our son Isaac\ and my other friends on the 20×24. How could I get more time on the camera? Subsidy by Polaroid was out of the question because the Artist Suppor t Program was besieged with requests. Renting the camera was costly. I thought about taking commissioned portraits on the 20×24 to cover the sub stantial rental cost but dismissed the idea as too scary. How would I fin d people to hire me? How could I take good portraits of people I didn’t know? I had been a photographer for eighteen years, photographing peop le I knew. Finally, encouraged by Harvey who kept on asking “what’s the worst that could happen?” I decided to go for it.

In 1981, after Harvey and I had renovated our house and Isaac was in kindergarten, I began renting the camera one day a month. The camera was a t the School of the Museum of Fine Arts and for the daily fee, I got film , the camera, the studio and the help of John Reuter, now the Director of Polaroid’s New York Studio.

The Museum School was nervous about young children and pets of any kind were absolutely forbidden. A huge obstacle was that the building was closed on Saturdays and Sundays. At the start of each monthly session, I had to set up the lights and the backdrop paper from scratch. When peopl e called, I’d have to say ” I’m only shooting on Thursday the 24th from nine to five. No animals.” It didn’t take long for me to see that I needed a camera in my own studio.

In the winter of 1987 I heard that one of the four other cameras was com ing back from Japan. I lobbied Eelco Wolf, Barbara Hitchcock, John McCa nn and Bob Chapman, at the Artists Support Program and the Large Format Department of Polaroid to lease it to me. One cold morning Harvey and I met Eelco outside 955 Mass Ave, a handsome eight-story office building a bout roughly equidistant from MIT, Harvard and the Polaroid Corporate Hea dquarters, to show him where I wanted to rent a studio that befitted the camera. Eelco considered the building, considered the location and considered the typed “business plan” I presented to him. He said he was willi ng to give me a chance. I took out a bank loan from the Cambridge Trust Co. where I had had an account since l96l, and bought lights. Thus I bec ame the only photographer to have a Polaroid 20×24 in her studio. (The others are in Edwin Land’s laboratory, and in Polaroid studios in New York, in Germany, and at Massachusetts College of Art.)

Eric Harrington and Alan Hess helped me set up my studio. Peter Bass taught me how to run the camera by myself. I went through two cases of fil m, almost eighty exposures, and made every mistake possible before I got a feel for the rhythm of the rollers and the timing of the motor. I bega n to understand that the colored “fringe” at the top of the image was made by the pod splitting open, that the black bar at the top and bottom of the image was from the rollers, that the chemicals at the bottom of the i mage were affected by how I peeled apart the image. I learned little tri cks of peeling apart and little tricks of timing. I got used to thinking of vertical images (the camera can’t work on the horizontal because of t he rollers). I learned to use filters to regulate the color of the film. I made notes on the floor of my studio so that I would know the right le ns setting for different distances from my subjects. Finally, on May 27t h, 1987, I was in business.

When my clients come off the elevator and I greet them in the hallway of my basement studio, I am reminded of a quote I found by Andre Breton: ” Seeing you for the first time, I recognized you without the slightest hesitation.” Instinctively, I find something familiar about the people I photograph, something recognizable, something that makes me like them. And they too on some level find something familiar about me that helps them relax and be comfortable with themselves and allow themselves to “be” in front of my camera and myself. There has to be some trace of the familiar for both me and my subject.

My studio, two rooms across the hall from each other in the basement of the building, is secluded . When I work on Saturdays and Sundays, the feeling of the space is cozy and womblike. I have covered the corridor walls with portraits to give clients a sense of the playfulness and the congeniality of my work. They are buoyed by seeing how other people’s sessions turned out and they get a few last-minute hints. They always look for people they may know–and most of the time they find someone. Even if they don’t know anyone, everyone looks familiar (partly because all the portraits are framed in grey-sided UV plexiglass boxes designed by Van Wood and partly because they are all ” signed” with the people’s first names in my own scrawl in India ink.) Even though there is no suggestion of place and everyone is standing on the same white paper, it is easy to place these people and to imagine the places they inhabit.

I do everything I can to make my subjects comfortable. By now I have certain rituals. I open up the camera and show them the rolls of negative a nd receiving paper. I show them the carpenters’ tape measure that indicates how far out the black cloth bellows are. I show them the bicycle chain that holds the pod tray. I explain how the pods of chemicals drop between the rollers when I hit a button. I have the client ceremoniously pull down the white seamless background paper with me. I lay down a line of white tape on which the client will stand. (It’s a comfortable space, about eight feet wide by two feet deep, warmed by the modelling lights, and about four feet from me and my camera.) I test the lights, holding my light meter in front of me as if I were saying a prayer. I operate the camera myself so we are alone. I try to have all my antennae working and to be like a sponge, absorbing their anxieties. Of course, to them I looklike I don’t have a care in the world. I look like an affectionate aunt caught in her kitchen looking for her favorite knife and brandishing her favorite dish towel. I pad around in stocking feet and always wear the same kitchen apron with two pockets for my focuser. I kneel on a green spongy garden pad when I guide the film out of the camera. I peel it on a work table loaded with tools and covered with chemical stains. But my authority over my work is total.

I want my people to look like they just stepped off the sidewalk into my studio, like they just dropped in. Familiar clothes, favorite clothes provide the gesture AND the characteristic habit. We know who we are and how we feel in familiar clothes. The clothes on the hanger look like us even when we’re not in them. The portrait begins in their closet.

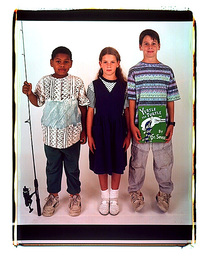

I remind them that they should bring favored objects that symbolize where they are in their lives and what is important to them. It’s always better to have too many props than to realize that the quintessential item was left at home. Props have run the gamut from rowing oars, diplomas, soccer balls, computers, books and records, a globe, skis, guitars, and stuffed animals to the Sunday night pizza. If they have pets–and the pets are part of the family and beloved by all (not always the case)–I encourage them to bring them. So I have done a teenage boy and his parakeet, an eight year old girl and her turtle, and a family with its bunny–as well as the usual assortment of cats and dogs. The act of thinking about props, of what to wear, of what defines them helps my subjects get ready for their session.

Most of my clients find me by word of mouth. They see my portraits in the living rooms, kitchens, and offices of their friends. The windows of the USTrust/Middlesex in Harvard Square, where I have a monthly display, at tracts many people. I also have a gallery/shop at Charles Square, next to the Charles Hotel, in Harvard Square where I have about eighty portraits on exhibit. Since there are so many connections between my clients, the gallery looks very familial.

Making portraits on commission is very different from inviting people to pose for me. I have not selected clients because they have great character, great humor, great faces, great posture, great clothes. The most critical act for a portrait photographer is the selection Of the subject. Diane Arbus, Richard Avedon, Robert Mapplethorpe, had an unerring eye for the right subject for them. When clients call me to take their portrait, I am completely dependent on how much of themselves they are willing or able to bring forth (and more to the po int, how much is there. In a good portrait, somebody has to be home.) My favorite subjects are people who accept themselves. They can stand in front of my huge camera and let themselves be, unchanged, just as they are, in a natural state. The Japanese have a word for this pose of total naturalness and total attention–sonomama.

I help the situation along by making sure that all my clients have seen my work before they actually make an appointment for a sitting. That way I get people who have a good idea of what I do and who can sense whether or not we could get a good portrait. I never convince people that they should commission me. I almost talk them out of it. One thing that people are hesitant about is that I take only two exposures. (Curiously, the portraits don’t get better, the more exposures are made.) I explain that if a person blinks, I absorb the cost and that if there is a technical flaw, like an incorrect exposure or a blip on the film, I absorb that cost too. Lots of people can’t stand the fact that I take only two exposures. Understandably, it makes them very nervous. I am left with people who are willing to go for it. People who whether they realize it or not have made a commitment to our portrait session. Because my subject and I see one exposure before we make the next exposure, the work is collaborative. There are people who find it very hard to collaborate. They don’t catch on and can’t relinquish their power. I used to exhaust myself trying to cajole such people. But now I relax and make a portrait of their stubborness.

Many of my portraits are about affection. People pose with people they love or they pose to make a portrait for people they love. Many siblings have their portraits taken for their parents’ twenty-fifth, thirtieth, fiftieth anniversary. (The most unusual groups of siblings were the seven O’Brien brothers–for their parents thirtieth–and Babe Parrott’s eleven children. Occasionally, spouses will take their mates on a special “date” and bring them to the studio as a surprise. When people come back to me every two years or four years, as several have, my portraits are about growing up, growing older, life changes. Many portraits incorporate an earlier portrait of my subject. Bernard Baumann posed on his eighty-fifth birthday with a blow up of a snapshot when he was an officer in the Polish army in 1927. Marybeth Walsh and her sister Patty posed with a color portrait taken in Bradlees exactly a decade earlier. On their fortieth anniversary Tom and Rosemarie Costin posed holding their wedding album with its hand tinted photograph cover. Danny Mazur posed on his thirtieth birthday with two black and white portraits of himself that I made in l965 and l970. I often say to people who have their portraits done on their tenth, thirteenth, sixteenth, or twenty-first birthdays, “This portrait is a message to yourself at forty. Look to the person you want to become.” There’s a whole group who come to celebrate their survival. Two fa- milies lived through awful car crashes; one family lost everything they owned in a fire. Two families, mother and college-age children, came on the anniversary of the husband/father’s death. Several people who had cancer–and who wanted a picture for the people they love, or with the people they love–came before they got really sick. What means the most to me, in all my picture-taking, is when someone tells me that their favorite picture of a loved one is the picture I took of them. My portraits have been at several memorial services and funerals–and in obituaries. After Paul Sutton’s memorial service along the banks of the Charles River, his friends went to my shop at Charles Square to see my portrait of Paul and his daughter Leila, taken in 1986. When I heard that I was very moved and very grateful that I had taken the picture.

I have a frank eye. It is open, makes contact, and doesn’t THREATEN. I am interested in the surface appearance of the person. I don’t try to strip off their so-called veneer. In fact, it is the veneer that attracts and charms me. I am perfectly comfortable with the idea that no portrait can ever be more than a version of the sitter. I don’t worry that my clients may have had a fight in the parking lot three minutes before they came off the elevator smiling at me.

As a photographer I am not interested in pointing my camera at the pathos of other people’s lives. I don’t try to reveal or to probe. I certainly don’t try to capture souls. (If any soul is revealed, it’s mine.) I am moved by the affection and the caring that people have for each other. On rare occasions I am upset by the anger and selfishness I am privy to during sessions. More often I am overwhelmed at how hard people are on themselves. They can’t forgive themselves for losing their hair or gaining weight or having eyes that are too small, too big, too widely spaced, too narrowly spaced. They won’t smile because there is a gap between their teeth. They are upset because their hair won’t lie flat (an obsession I attribute to the hair style of TV anchor people). In those circumstances I try to comfort my sitter into a moment of acceptance and pray that my portrait will show them that they are more than their offending teeth, hair. etc. Within families there is a web of relationships–but I don’t want to convey uneasiness or distress in the portraits. Instead, I want to create with my subject the evidence that they are surviving and prevailing. I see my family portraits — and especially the megafamily portraits of several siblings and spouses and children– as proof of affectionate endurance.

The portraits that I take on commission and the portraits I take for myself have come to look the same and feel the same to me. My portraits of Allen Ginsberg have been continuing since that first session in 1980. My first self-portrait was during that session, too. I make self portraits on my birthday and every now and then when I have only one shot left in the case of film. (I think it is good for me to experience what my subjects are going through–and it is wild to see how I have changed over ten years.) My first portrait of Harvey and Isaac was in 1981–and I take at least one every year. Since 1981 when Isaac was in kindergarten I have taken portraits of the children in his class at the Martin Luther King Open School in Cambridge. Young people who come to my studio ask me if I get bored taking portraits. The question stops me in my tracks. The answer, after thought, is that I don’t get bored. I think it is because the people are all different. And the people are wonderful and eager and glad to be there. I do get scared though, that I won’t get a good portrait, that I won’t be as good as I have been. I do worry more than about how the portrait will be than I did when I started out.

For me the key word is “apparently.” All I hope my photographs say is this person lives and this person was here.