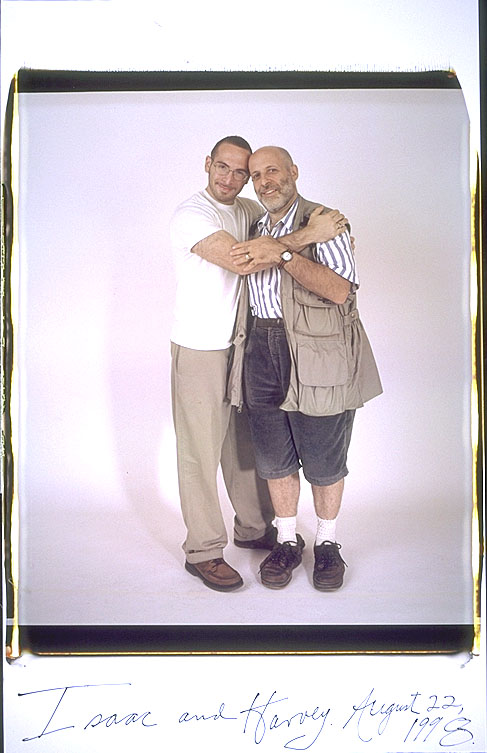

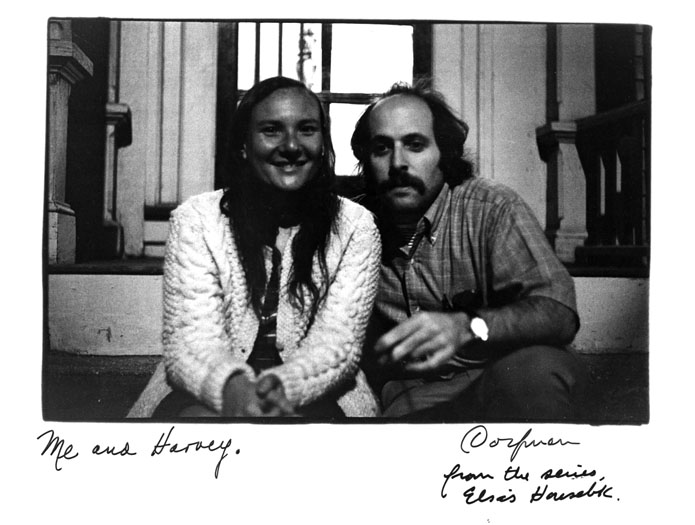

Silverglate

I always know it’s Harvey Silverglate by the way he rings the doorbell. It’s very short, the way you ring when you’re sure the person isn’t home, I’ve known him since fall 1967, when he was the defense attorney in Boston’s first big marijuana trial. I had the idea that the transcript of that trial and all the expert testimony would make a great book, so I made an appointment to see him. He sat me in his office with a huge file of press clippings and notes, and when I left, he said that some day I’d have to take a picture of him and his brother for his mother. I went home and looked in the phone book to see if he lived near me.

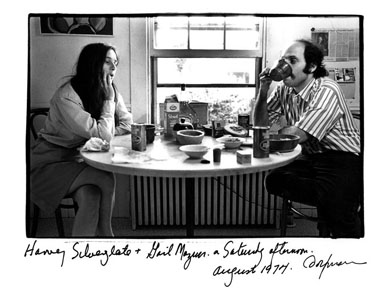

The next time we saw each other was February 1968 when Allen Ginsberg came to read for the Harvard SDS chapter. Allen was all involved in legislation to legalize marijuana, and wanted to compare notes with Harvey (whom he’d heard about from several people], so we called Harvey at one in the morning to come to the party we were at. The next week, Harvey came to my house for supper. He was two hours late and brought me a Wetzstein’s New York kosher salami that was twenty-seven inches long. I made a roast beef — rare — and fresh mushrooms; Harvey didn’t tell me that he can’t stand either red meat or vegetables. Since then, we’ve been together and broken up several times.

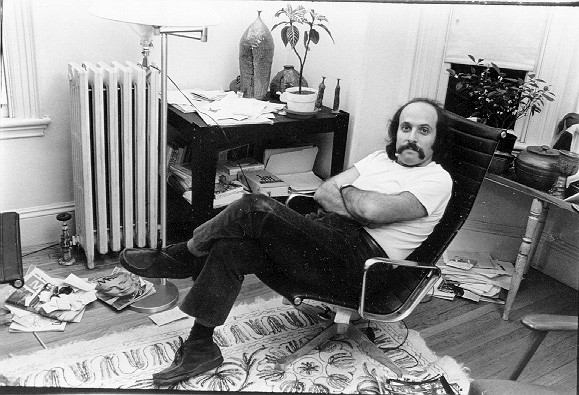

In October 1973, Harvey moved to Flagg Street, three houses away from me. We work all the time, are news addicts, walk around the Square looking at bookstore windows, talk about working less, go to the movies, jog by the Charles River, go to restaurants for Szechuan Chinese food, sit on the front stoop. Because the criteria and pressures of our work are so different, Harvey and I spend a lot of time explaining to each other what is going on, what matters. Sometimes I wish he were a photographer too or a novelist (a presumption since he’s such a rare and creative criminal lawyer). We have separate sets of friends and though we often see them together, we each spend a lot of time with them by ourselves. And up to now, we’ve never mixed them, his with mine. Whenever I have my friends over, Harvey runs out in the middle of the evening for rum and lemons so he can make his marvelous daiquiris for everyone — or for homemade pies — apple, cheese, pecan, blueberry.

Our fights are about coupling, distance, intimacy, the real/imagined demands of our work, how we each think we should live. We have them every couple of months; they’re quiet, almost monosyllabic. Harvey provides the situation and I provide the words. After about a day and a half we’re hack together as if nothing happened; we usually make the remedies but we never talk about what just passed.

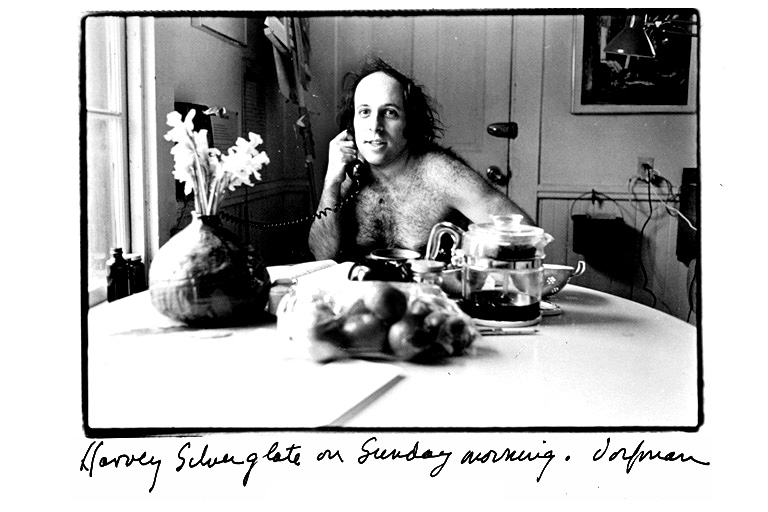

I love taking pictures of Harvey, partly because it’s a switch on the usual combination — male photographer, female lover. I take pictures of him at the typewriter in his office, with his friends, naked in hotel rooms, rushing into surf at Nantucket, with his relatives in Miami. [The one place I can’t bring my camera is the courtroom; it’s against the law in Massachusetts.) Harvey is accustomed to my camera’s being there, but occasionally he feels it’s an intrusion. After all, he says, though it looks easy — aim, focus, snap — it is work, and I’m not all there when I have it in hand. It’s a screen of sorts; I’m using it to distance myself from other people. And besides, he likes to add, there has to come a time when the things around me are not, at least for a little while, material. My response to all this is always mixed; I think I’m using the camera for exactly the opposite reason, to be involved. The thought of having to leave my camera behind for someone else’s reasons, his, makes me feel trapped/resentful/rebellious: oh yeah, well, I’m taking my 4×5, so there. The two or three times this issue has come up, I’ve said, ‘OK, I won’t go through the whole number; I’ll put my Pentax [a smallish camera] in my pocketbook.’ And when I felt like it, I used it.